Women Kendo Luminaries:

There are a number of women in kendo that continue to strive achieving personal goals and supporting the growth of kendo in their countries post their national team careers and amidst work/family commitments. This is the second (02) article under the category “Women Kendo Luminaries” that acknowledges the perspectives, achievements, and contributions of women in kendo from around the world.

02 Dance Yokoo (Germany)

(Introduction by Kate Sylvester)

The German women’s national team was the first European women’s team to break through to medal standings, which occurred at the World Kendo Championships (WKC) in Taiwan in 2006. It is no coincidence that 7 dan Dance Yokoo sensei of Germany played a major role in the team’s winning streak at both the WKC and European Kendo Championships (EKC) during her 10-year national team career. The German women’s team continue to be successful and respected.

The female population of German kendo is healthy standing at 588, which is 22% of the total membership. Some contributing factors related to the high number are likely to be connected to the women’s national team’s ongoing success and also that there are durable women role models such as Dance Yokoo who are striving to not only improve their kendo but are also in leadership roles.

As mentioned in previous articles, it is crucial that high-level women are visible and appointed in leadership positions in kendo especially considering the few high-graded women over the age of 40 are active in kendo internationally outside of Japan. After all, kendo is a lifelong physical activity and a significant number of high-graded women in Japan practice kendo well into their golden years. The presence of highly skilled and driven women kendoka such as Dance Yokoo are important role models for women and men and as such, are precious assets of kendo federations.

The first time I spoke to and trained with Yokoo was in Hungary in 2022 before the National Gathering Shiai. Although Australia fought Germany in the team competition at the 2003 WKC, and we had attended other WKC together, I had never spoken to Yokoo. I had followed Yokoo on social media and was in awe of how serious and committed to kendo she was. Her posts were motivational, and nagged my consciousness that I need to be training more and working harder to improve. Last year, when I first met Yokoo I recall feeling an instant nervous excitement and respect. I was quietened by her powerful and calm aura/ki (presence). It was a little intimidating but positive in a way that incites focus and growth. All this mental assessing was occurring even before our keiko.

Yokoo’s kendo is intuitive, sound, and technically strong. As we practiced together, her footwork out stepped mine and I soon felt her kendo knowledge was deep. She viscerally communicated that my kendo lacked aiki (connection) and riai (rationality). Training with Yokoo reminded me of training in Japan and this level of training focus is one that I value, although it is very hard to practice. Outside of Japan, it is quite difficult to maintain the focus of aiki and riai as I find often people focus on hitting-without connection or logic. After keiko, I asked for advice and Yokoo gave me the advice I expected. I was quite relieved kendoka outside of Japan focuses on these important aspects and it guided me back to my path.

That weekend in Hungary, I also observed Yokoo’s referee skills. She demonstrated an elevated skill set and held herself with the type of deportment that promotes confidence in shiaisha (competitors) which we know is critically important as it draws out the best performances and leads to an acceptance of referee decisions. Personally, I would have great confidence and a sense of reassurance if Yokoo was either a shinpan or grading panel member that I was performing in front of. Even if I lost or failed, I would trust it was the right decision.

This sentiment speaks volumes of Dance Yokoo as over my 30-year kendo career I have had been very fortunate to train and compete with and be taught by the best of the best in the world. Needless to say, I have a high level of respect for Dance Yokoo and feel grateful that there is such a person (non-gender specific) that is so serious and committed to kendo in such an authentic and inspiring way.

Photo: Deggendorf (Germany) kendo seminar 2016

About Dance Yokoo (Germany)

Dance Yokoo sensei is 7 dan and has been a kendo instructor at Kendo München for the past 17-years. As a national team member for 10-years, she has had an astounding competitive career winning several medals at the national championships (Gold in 2017, 2010, 2006, 2002. Silver in 2022, 2021, 2019, 2014, 2012, 2009. Bronze in 2011, 2007, 2005). As a member of the national team, the women had great success at the EKC winning gold in 2013, 2011, 2008, 2007, 2005 and silver in 2010 and 2004. Notably the women’s team won bronze at the 2006 and 2012 WKC in the team events. In addition, she has also received 3 fighting spirit awards. Once at the EKC (2005) and twice at the WKC (2006 and 2012).

Photo: Team Germany at the 2012 WKC in Italy

Yokoo continues to compete, which she explains, maintains, and improves her refereeing skills. She is also the main referring officer with the German Kendo Federation and oversees a system that requires shinpan to be accredited before they can shinpan at certain competitions. Outside of kendo, Yokoo is a talented graphic artist having created the popular 2022 EKC tenugui. As you will read in the following passages, Yokoo sensei’s perspective and experiences on kendo are rich and they reveal a depth to her kendo that most of us ordinary practitioners are ardently pursuing. The rest of the article are responses to a series of questions that are answered in Yokoo’s own words.

Please share a little about your life outside of kendo.

I am a graphic designer by profession, but for almost 7-years I’ve been working in completely different fields like textiles and trading for a Japanese company in Munich. Our company has over 125-years of history of trading and we’re selling fabrics and producing final garments for European brands, and we also export Japanese products to European customers.

Nevertheless, I’m still creating some design works sometimes, especially for my kendo friends when they need for example new club logos or tenugui for some events. For the last EKC in Frankfurt 2022, I had the honour of designing the tenugui for this event and I hope many kendoka in Europe are using it right now.

How did you start kendo?

“It was brainwashing”

I have often been asked how I originally started kendo. Each time I have to feel a little embarrassed because compared to many other kendo people all over the world, my reason for starting kendo is quite different and not serious at all.

Well, it all started like this. A very good artist friend of my father, Mr. Nakabayashi, from Hokkaido Japan, often visited our home when I was still a little girl. Mr. Nakabayashi had 4 dan at that time I think, and his grandfather was once the president of the Hokkaido Kendo federation, I heard. Anyway, each time when Mr. Nakabayashi was at our home, he was telling me stories like, “Dance, do you know that all the pretty women in Japan are practising kendo? So, it’s a must for you to start with kendo someday”.

Over the years, he successfully manipulated my young mind, my brain, and I finally started with kendo when I got to junior high school in Japan in 1990. After about a year, I had to make a little kendo break about a year because my mother, Anzu Furukawa, a Butoh Dancer, got a 6-year contract at the Art University in Braunschweig in Germany and we had to prepare a lot of things before we moved to Germany with the whole family.

It must have been in winter 1991 when we finally moved to Braunschweig shortly before my fourteenth birthday. At that time my brother Kyota was also practising kendo and we both visited the kendo club, Kyumeikan Dojo in Braunschweig. I did all my exams from 6 kyu to 4 dan in Germany, so you can definitely say I was trained in Germany. My brother stopped Kendo in 1993 because he couldn’t stand learning Japanese culture from a 3 dan German sensei. I was a little lucky that I was 5-years older and could keep my interest in kendo a little longer until I met my very first Bundestrainer from Japan, Haga Tadashi sensei from Saitama Police between 1993 and 1994.

If I hadn’t met Haga sensei at that time, I probably would have stopped with kendo like my younger brother. Haga sensei was the first “player coach” I met, and it means that he basically he practised the whole training with us, I mean with beginners and children like me at that time.

He was a great motivator and showed us all how much fun it could be at kendo practice. He also taught me how important it is to practise with strong people. He compared it to painting colours, where all the strong people are a big bucket of red and I am just one drop of white. What happens when this drop of white colour gets into the bucket of red colour? Well, you can guess, right?

So, from the bottom of my heart, thank you so much Haga sensei. For giving me and showing me such passion and love for kendo.

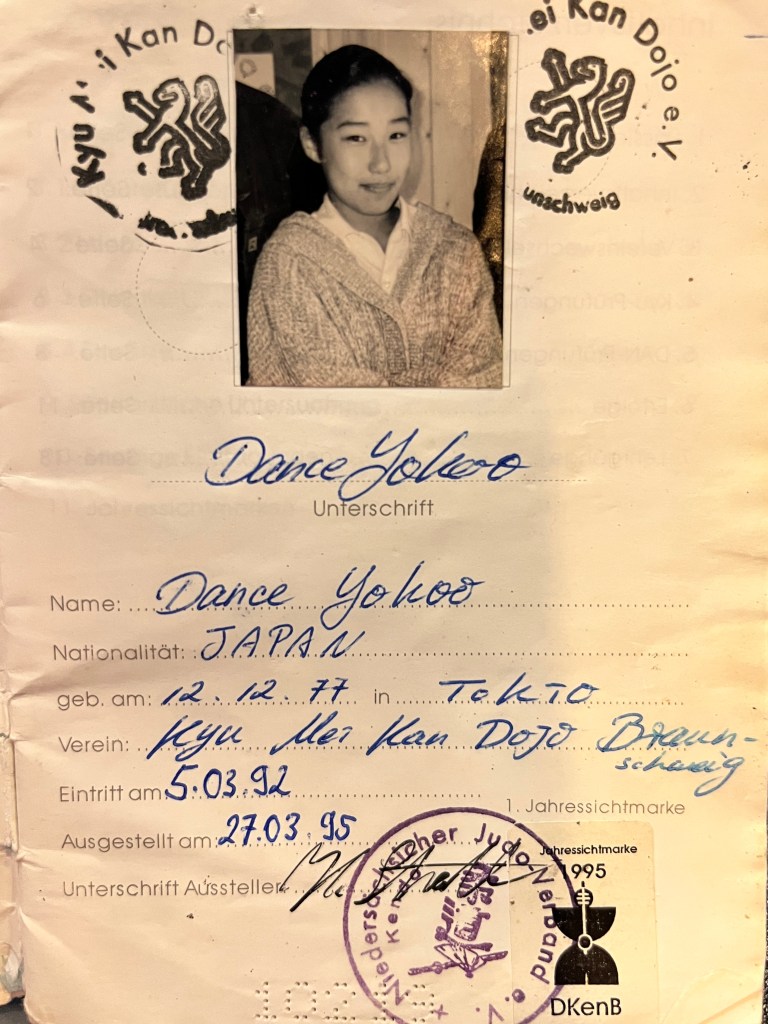

Photo: The grading card of Dance Yokoo in 1995

I have noticed that you still compete. Please share a little about what inspires you to keep competing although you are no longer a national team member.

Unfortunately, there are not many competitions in Europe where kendoka of similar age can fight against each other like in Japan. In Japan there are so many competitions for men and women with different age categories. For example, there are team competitions with 3 fighters and age categories such as, under 100-years, 101 to 150-years, over 151-years (the age categories are the accumulated age of all members). There are also individual championships with age categories such as 18 to 29-years, 30 to 39-years, 40 to 49-years, 50 to 59-years and so on.

However, there is no reason to stop competing after a national team career, because Japanese competitors don’t stop fighting either. All the sensei from young to old, whom I respect are fighting and developing further both as competitors and as shinpan and I would like to follow the same path like them. I believe also that only in this way it is possible to keep up in the matter of shiai to become a good shimpan. Besides that, in kendo it is often said that you should practise like if you were in the shiai at your daily keiko and this is only possible if you’re actually doing shiai often enough.

What is your competitive career highlight?

My best performance was probably at the WKC in Taiwan 2006 when I was 28-years-old. The German women’s team was together with Team Korea and USA in the group stage, and we just had to win against one of those strong teams (2nd and 3rd placed teams) to be able to reach the knockout rounds.

Against Team USA we won 2 – 0 and I scored two ippons as Fukusho! Against Team Korea we lost 2 – 4 and here I was also able to score two ippons and the whole team shiai was very close until the end. At the quarterfinal we fought against Chinese Taipei and at the end the fight had to be decided with the daihyosen (playoff match) and thank god our captain, Kei Udagawa, could bring Team Germany into the semi-final against Japan.

Photo: Team Germany at the 2006 WKC in Taiwan

At the semi-final against Team Japan, my match was a hikiwake (draw) and as the first European female team that achieved 3rd place at the WKC. It was absolutely awesome. So, I always say that it doesn’t matter how strong your opponents are, as a team you have always chances to win if everyone in the team really sticks together and fights for it.

I actually can’t remember how I fought at the individual championship but somehow, I received Fighting Spirit Award (kantosho), so it must have been good, I guess. So, all in all, this WKC in Taiwan was one of the greatest championships I have ever had.

Please share a special kendo experience.

“Aura/Ki and Colour”

Can you believe me if I tell you that there are auras/ki that can change the colour of the air around? Well, at one of the high-level kendo seminars in Deggendorf in Germany 2016 Ujiie Michio Sensei 8 dan hanshi and Kiyono Shinobu sensei 8 dan kyoshi from Japan were the invited sensei. I still can remember about that day, that moment when Ujiie sensei entered the hall with his long black down jacket. Suddenly it looked as if the air around him or even the whole atmosphere became a light purple colour.

I couldn’t believe what I was seeing and after some moments the colour just disappeared, but I couldn’t move for a moment. It happened just that once and it was a kind of magical moment and experience for me.

Later, I had a keiko with Ujiie sensei and I really loved that aiki (connection) with him and I think he felt quite similar and he said that it was great for him that I wasn’t willing to hit but willing to have aiki with him. He explained that everybody was trying “just to hit” and it bored him. So, I was quite happy that I could have a keiko, which he also enjoyed.

Sometimes I get this similar enjoyment even during a competition and I just want to keep fighting with my opponent, which could also be a little problem if you actually wanted to win the fight!

Please share why you decided to attempt 7 dan in Japan and also a little about your journey to passing 7 dan.

“The last one must be in Japan!”

In Germany you can do your dan examinations up until the 5 dan in our own country. However, I once watched a 5 dan examination at our yearly kangeiko (winter training camp) with a Japanese sensei and he gave me the feeling that people from the national team can easily pass the exam without showing outstanding performances.

His statements were understandable on the one hand and on the other hand somewhat also hurtful for me because I had also taken my exams until 4 dan in Germany. So, this experience made me think and I did all my following exams outside of Germany. I passed 5 dan exam at the EKC in Helsinki in 2008 and 6 dan at the EKC in 2013 in Berlin.

In Germany we have great role model sensei like Ralph Lehmann or Jörg Potrafki, who passed their 7 dan in Japan and they are still continuing kendo. Ralph was our national team coach for a long time and Jörg was my sensei when I was practising in Berlin for over 6-years. All the sensei I highly respect have passed their 7 dan in Japan of course, in the country where not even an All Japan Champion can pass the 7 dan for the first time sometimes!

I’m telling this because on the day when I passed my examination, there was also a former All Japan champion on the youngest court and he unfortunately couldn’t pass.

For me it was also proof that I’m capable of passing my exam even when I was compared with Japanese kendoka at my age. And I just wanted to pass my 7 dan on the same stage as all the sensei I admire and also for my confidence. Furthermore, the 7 dan grade is the very last one, which I could possibly pass if I practise diligently. After all, there are no female 8 dan yet, not even in Japan.

Photo: Dance Yokoo celebrating 7 dan with Kendo München

Do you think there is gender inequality in kendo? If yes, can you provide some suggestions to how these issues can be improved upon?

In the history of traditional sword fighting in Japan, kendo is one of the youngest and quite new and the name “kendo” has existed for a little longer than 100-years by now. In the old sword schools, there was often the case that female participants were not allowed. They were even not allowed to enter the dojo. When I think of this, kendo is much more open nowadays but of course there is still no female 8 dan and we haven’t had any female referees at the WKC, for example. So, there is obviously still a problem of gender inequality in kendo.

However, I have to admit that I’m personally more a fan of male kendo style and I never had a chance to meet a female sensei that is as strong as male sensei, so I can’t really say if the reason why there still isn’t a female 8 dan is really because of the gender inequality.

At the same time, as I already mentioned before, that the history of “kendo” is quite young and nowadays there are female sensei slowly emerging, who practise kendo just as professionally, long and intensively like male sensei, and probably have the potential to attain the highest dan degree, 8 dan, accordingly. So, there could soon be the very first female 8 dan, hopefully.

The German Kendo Federation (Deutscher Kendobund – DKenB) have a well organised referee licencing system in place. Can you tell us about this system?

The department for referees within the federation was long managed by Dr. Paul-Otto Forstreuter (7 dan kyoshi) and was later taken over for a while by Dido Demski (6 dan). While Dido Demski took over the task, I was allowed to take on some tasks as her assistant and after about two years I officially took over the department. I have therefore been responsible for referee training in Germany since 2020 as well as for all referee allocations for German championships and licence extensions etc.

We have theory classes online and also at championships and practical seminars at championships.

In Germany we have a structured referee licence system. We have two different kind of licences. Landeskampfrichter (for refereeing on a county level) and Bundeskampfrichter (for refereeing on a national level).

The requirements to obtain a Landeskampfrichter licence:

1. has reached the age of 18 at least.

2. has reached the age of 65 at the most.

3. holds at least the 2 dan kendo.

4. has attended a basic course for state referee candidates and an advanced course for state referee candidates within the last 24 months prior to the examination, whereby participation in only one “referee course” according to § 7 paragraph 2 of these regulations does not meet the requirements.

5. has had at least two referee assignments at state tournaments or competitions of at least equal importance in the last 24 months.

6. has gained experience as a competitor.

The examination is divided into a written examination, an oral examination and a practical examination through the use at a tournament.

For the extension of the national referee licence, the national referee must have participated in at least two events as a national referee and in one further training event within a period of 24 months. The deadline is 31 December of the last year of validity. The renewal takes place from the end of the last year of validity.

The extension of the licence requires active participation in kendo training.

The requirements to obtain a Bundeskampfrichter licence:

1. has reached the age of at least 25 years.

2. has reached the age of 65 at the most.

3. has been awarded at least the 4 dan kendo.

4. has held a State Referee Licence for at least three years and has officiated at least ten times at state tournaments or competitions of at least comparable size and importance during this period.

5. has attended two training courses for aspiring federal judges within the last 24 months prior to the examination.

6. has gained experience as an active competitor.

The examination is divided into a written examination, an oral examination and a practical examination through the use at a tournament. For the licence extensions you need to take part in a DKenB recognised referee seminar within 24 months.

Please share a little about your EKC shinpan experience. Do you have the aspiration to shinpan at the WKC?

Apparently, it is not clear if female 7 dan can be selected as shinpan for the WKC. For example, at the recent shinpan seminar in Brussels, a leading sensei joked saying a women would only be able to participate at the upcoming WKC as a competitor. I was taken back by this comment.

I had the honour of being selected as a shinpan for the last EKC in Frankfurt 2022. I was of course a little excited standing on stage of such a big competition on the shiaijo (competition arena) but I really loved it being directly at the shiai and to be able to judge the fights.

Luckily, we had the fights of the semi-finals for the junior and men’s division on our shiaijo, so I could judge shiai for those competitors and I really loved being so near to the fight. I hope that all the fighters I had at the shiaijo were happy with our performances. Please remember our faces with good memories. I’m saying this, because Koda Kunihide sensei always tells us that people never forget the faces of bad shinpans.

I had a memorable experience at the sayonara party of the last EKC in Frankfurt when I received really nice feedback from a female fighter. She explained that she was happy when she saw me as shushin (head judge on court) when she fought and she felt secure and had a feeling that nothing strange would happen when I was refereeing. Unfortunately, I wasn’t selected for the next upcoming EKC in France, but I wish all the referees and fighters all the best and a great championship. I’ll be there to cheer for all of you.

What motivates you to keep improving in kendo?

I’ve been in love with kendo for so long. Longer than any of my other relationships. As long as I can enjoy having keiko, I’ll be in practice, so that I can really be able to enjoy it. It’s a circle of kendo life. I think this is what we call 生涯剣道 or “shogai-kendo” or “lifetime kendo”.

Do you have any words of wisdom that may inspire others to keep striving in kendo?

The sword is the mind.

If the mind is not right, the sword is also not right.

If you wish to learn swordsmanship, first learn it from the heart (kokoro).

By Toranosuke Shimada

(Along with Otani Nobutomo and Oishi Susumu, he was considered one of the three greatest swordsmen of the end of the Edo period. He called himself a member of the Shimada school (島田派) of Jikishin Kage-ryu (直心影流). In addition to swordsmanship, Toranosuke also liked to study Confucianism and Zen)

其れ剣は心なり。

心正しからざれば、

剣又正しからず。

すべからく剣を学ばんと欲する者は、

まず心より学べ

島田 虎之助

All photographs in this article were provided by Dance Yokoo.